Miklós Horthy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya ( hu, Vitéz nagybányai Horthy Miklós; ; English: Nicholas Horthy; german: Nikolaus Horthy Ritter von Nagybánya; 18 June 1868 – 9 February 1957), was a Hungarian

Miklós Horthy de

Miklós Horthy de

* 1896 ''

* 1896 ''

Kun and his henchmen proclaimed a

Kun and his henchmen proclaimed a  Following the pressure of the Allied powers, Romanian troops finally evacuated Hungary on 25 February 1920.

Following the pressure of the Allied powers, Romanian troops finally evacuated Hungary on 25 February 1920.

The first decade of Horthy's reign was primarily consumed by stabilizing the Hungarian economy and political system. Horthy's chief partner in these efforts was his prime minister

The first decade of Horthy's reign was primarily consumed by stabilizing the Hungarian economy and political system. Horthy's chief partner in these efforts was his prime minister

For Horthy, Hitler served as a bulwark against Soviet encroachment or invasion. Horthy was obsessed with the Communist threat. One American diplomat remarked that Horthy's anti-communist tirades were so common and ferocious that diplomats "discounted it as a phobia".

Horthy clearly saw his country as trapped between two stronger powers, both of them dangerous; evidently, he considered Hitler to be the more manageable of the two, at least at first. Hitler was able to wield greater influence over Hungary than the Soviet Union could – not only as of the country's major trading partner but also because he could assist with two of Horthy's key ambitions: maintaining Hungarian sovereignty and satisfying the nationwide yearning to recover former Hungarian lands. Horthy's strategy was one of cautious, sometimes even a grudging, alliance. The means by which the regent granted or resisted Hitler's demands, especially with regard to Hungarian military action and the treatment of Hungary's Jews, remain the central criteria by which his career has been judged. Horthy's relationship with Hitler was, by his own account, a tense one – largely due, he said, to his unwillingness to bend his nation's policies to the German leader's desires.

Horthy's attitude to Hitler was ambivalent. On one hand, Hungary was an

For Horthy, Hitler served as a bulwark against Soviet encroachment or invasion. Horthy was obsessed with the Communist threat. One American diplomat remarked that Horthy's anti-communist tirades were so common and ferocious that diplomats "discounted it as a phobia".

Horthy clearly saw his country as trapped between two stronger powers, both of them dangerous; evidently, he considered Hitler to be the more manageable of the two, at least at first. Hitler was able to wield greater influence over Hungary than the Soviet Union could – not only as of the country's major trading partner but also because he could assist with two of Horthy's key ambitions: maintaining Hungarian sovereignty and satisfying the nationwide yearning to recover former Hungarian lands. Horthy's strategy was one of cautious, sometimes even a grudging, alliance. The means by which the regent granted or resisted Hitler's demands, especially with regard to Hungarian military action and the treatment of Hungary's Jews, remain the central criteria by which his career has been judged. Horthy's relationship with Hitler was, by his own account, a tense one – largely due, he said, to his unwillingness to bend his nation's policies to the German leader's desires.

Horthy's attitude to Hitler was ambivalent. On one hand, Hungary was an  Three months later, after the

Three months later, after the  But despite their cooperation with the Nazi regime, Horthy and his government would be better described as "conservative authoritarian" than "fascist". Certainly, Horthy was as hostile to the home-grown fascist and ultra-nationalist movements that emerged in Hungary between the wars (particularly the

But despite their cooperation with the Nazi regime, Horthy and his government would be better described as "conservative authoritarian" than "fascist". Certainly, Horthy was as hostile to the home-grown fascist and ultra-nationalist movements that emerged in Hungary between the wars (particularly the  And yet, by the time of this episode, Horthy had allowed his government to give in to Nazi demands that the Hungarians enact laws restricting the lives of the country's Jews. The first Hungarian anti-Jewish Law, in 1938, limited the number of Jews in the professions, the government, and commerce to twenty percent, and the second reduced it to five percent the following year; 250,000 Hungarian Jews lost their jobs as a result. A "Third Jewish Law" of August 1941 prohibited Jews from marrying non-Jews and defined anyone having two Jewish grandparents as "racially Jewish". A Jewish man who had non-marital sex with a "decent non-Jewish woman resident in Hungary" could be sentenced to three years in prison.

Horthy's personal views on Jews and their role in Hungarian society are the subjects of some debate. In an October 1940 letter to Prime Minister

And yet, by the time of this episode, Horthy had allowed his government to give in to Nazi demands that the Hungarians enact laws restricting the lives of the country's Jews. The first Hungarian anti-Jewish Law, in 1938, limited the number of Jews in the professions, the government, and commerce to twenty percent, and the second reduced it to five percent the following year; 250,000 Hungarian Jews lost their jobs as a result. A "Third Jewish Law" of August 1941 prohibited Jews from marrying non-Jews and defined anyone having two Jewish grandparents as "racially Jewish". A Jewish man who had non-marital sex with a "decent non-Jewish woman resident in Hungary" could be sentenced to three years in prison.

Horthy's personal views on Jews and their role in Hungarian society are the subjects of some debate. In an October 1940 letter to Prime Minister

The

The

By 1944, the Axis was losing the war, and the

By 1944, the Axis was losing the war, and the

admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

and dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in times ...

who served as the regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

of the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

between the two World Wars and throughout most of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

– from 1 March 1920 to 15 October 1944.

Horthy started his career as a sub-lieutenant

Sub-lieutenant is usually a junior officer rank, used in armies, navies and air forces.

In most armies, sub-lieutenant is the lowest officer rank. However, in Brazil, it is the highest non-commissioned rank, and in Spain, it is the second high ...

in the Austro-Hungarian Navy

The Austro-Hungarian Navy or Imperial and Royal War Navy (german: kaiserliche und königliche Kriegsmarine, in short ''k.u.k. Kriegsmarine'', hu, Császári és Királyi Haditengerészet) was the naval force of Austria-Hungary. Ships of the A ...

in 1896 and attained the rank of rear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

in 1918. He saw action in the Battle of the Strait of Otranto and became commander-in-chief of the Navy in the last year of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

; he was promoted to vice admiral and commander of the Fleet when Emperor-King Charles dismissed the previous admiral from his post following mutinies. During the revolutions and interventions in Hungary from Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

, and Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

, Horthy returned to Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

with the National Army; the parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

subsequently invited him to become regent of the kingdom. Through the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

Horthy led an administration which was national conservative

National conservatism is a nationalist variant of conservatism that concentrates on upholding national and cultural identity. National conservatives usually combine nationalism with conservative stances promoting traditional cultural values, f ...

. Hungary under Horthy banned the Hungarian Communist Party

The Hungarian Communist Party ( hu, Magyar Kommunista Párt, abbr. MKP), known earlier as the Party of Communists in Hungary ( hu, Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja, abbr. KMP), was a communist party in Hungary that existed during the interwar ...

as well as the Arrow Cross Party

The Arrow Cross Party ( hu, Nyilaskeresztes Párt – Hungarista Mozgalom, , abbreviated NYKP) was a far-right Hungarian ultranationalist party led by Ferenc Szálasi, which formed a government in Hungary they named the Government of National ...

, and pursued an irredentist

Irredentism is usually understood as a desire that one state annexes a territory of a neighboring state. This desire is motivated by ethnic reasons (because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to the population of the parent sta ...

foreign policy in the face of the 1920 Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (french: Traité de Trianon, hu, Trianoni békeszerződés, it, Trattato del Trianon) was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in ...

. Charles, the former king, attempted twice to return to Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

before the Hungarian government caved in to Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

threats to renew hostilities in 1921. Charles was then escorted out of Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

into exile.

Ideologically a national conservative

National conservatism is a nationalist variant of conservatism that concentrates on upholding national and cultural identity. National conservatives usually combine nationalism with conservative stances promoting traditional cultural values, f ...

, Horthy has sometimes been labeled as fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

. In the late 1930s, Horthy's foreign policy led him into an alliance with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

against the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. With the support of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, Hungary succeeded in redeeming certain areas ceded to neighboring countries by the Treaty of Trianon. Under Horthy's leadership, Hungary gave support to Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

refugees in 1939 and participated in the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Some historians view Horthy as unenthusiastic in contributing to the German war effort and the Holocaust in Hungary

The Holocaust in Hungary was the dispossession, deportation, and systematic murder of more than half of the Hungarian Jews, primarily after the German occupation of Hungary in March 1944.

At the time of the German invasion, Hungary had a Jewis ...

(out of fear that it may sabotage peace deals with Allied forces), in addition coupled with several attempts to strike a secret deal with the Allies of World War II

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy. ...

after it had become obvious that the Axis would lose the war, therefore eventually leading the Germans to invade and take control of the country in March 1944 in Operation Margarethe

Operation Margarethe (''Unternehmen Margarethe'') was the occupation of Hungary by German Nazi troops during World War II that was ordered by Adolf Hitler.

Course of events

Hungarian Prime Minister Miklós Kállay, who had been in office from ...

. However, prior to the Nazi occupation within the area of Hungary 63,000 Jews were killed. In late 1944, 437,000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where the majority were gassed on arrival. Serbian historian Zvonimir Golubović has claimed that not only was Horthy aware of these genocidal massacres, but had approved of them such as those in the Novi Sad Raid

The Novi Sad raid, also known as the Raid in southern Bačka, the Novi Sad massacre, the Újvidék massacre, or simply The Raid ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Рација, Racija), was a military operation carried out by the Királyi Honvédség, the armed for ...

.Zvonimir Golubović, Racija u Južnoj Bačkoj, 1942. godine, Novi Sad, 1991. (page 194)

In October 1944, Horthy announced that Hungary had declared an armistice with the Allies and withdrawn from the Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

. He was forced to resign, placed under arrest by the Germans and taken to Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

. At the end of the war, he came under the custody of American troops. After providing evidence for the Ministries Trial

__NOTOC__

The Ministries Trial (or, officially, the ''United States of America vs. Ernst von Weizsäcker, et al.'') was the eleventh of the twelve trials for war crimes the U.S. authorities held in their occupation zone in Germany in Nuremberg af ...

of war crimes in 1948, Horthy settled and lived out his remaining years in exile in Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

. His memoirs, ''Ein Leben für Ungarn'' (''A Life for Hungary''), were first published in 1953. He has a reputation as a controversial historical figure in contemporary Hungary.

Early life and naval career

Miklós Horthy de

Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya

Baia Mare ( , ; hu, Nagybánya; german: Frauenbach or Groß-Neustadt; la, Rivulus Dominarum) is a municipality along the Săsar River, in northwestern Romania; it is the capital of Maramureș County. The city lies in the region of Maramureș ...

was born at Kenderes to an untitled lower nobility, descended from István Horti, ennobled by King Ferdinand II

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

in 1635. His father, István Horthy de Nagybánya, was a member of the House of Magnates

The House of Magnates ( hu, Főrendiház) was the upper chamber of the Diet of Hungary. This chamber was operational from 1867 to 1918 and subsequently from 1927 to 1945.

The house was, like the current British House of Lords, composed of hered ...

, the upper chamber of the Diet of Hungary

The Diet of Hungary or originally: Parlamentum Publicum / Parlamentum Generale ( hu, Országgyűlés) became the supreme legislative institution in the medieval kingdom of Hungary from the 1290s, and in its successor states, Royal Hungary and ...

, and lord of a estate. He married Hungarian noblewoman Paula Halassy de Dévaványa in 1857. Miklós was the fourth of their eight children raised as Protestants.

Horthy entered the Austro-Hungarian Imperial and Royal

The phrase Imperial and Royal (German: ''kaiserlich und königlich'', ), typically abbreviated as ''k. u. k.'', ''k. und k.'', ''k. & k.'' in German (the "und" is always spoken unabbreviated), ''cs. és k. (császári és királyi)'' in Hungari ...

Naval Academy (k.u.k.

The phrase Imperial and Royal (German: ''kaiserlich und königlich'', ), typically abbreviated as ''k. u. k.'', ''k. und k.'', ''k. & k.'' in German (the "und" is always spoken unabbreviated), ''cs. és k. (császári és királyi)'' in Hungari ...

Marine-Akademie) at Fiume (now Rijeka

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Primor ...

, Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

) at age 14. Because the official language of the naval academy was German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, Horthy spoke Hungarian with a slight, but noticeable, Austro-German accent for the rest of his life. He also spoke Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

, Croatian, English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

, and French.

As a young man, Horthy traveled around the world and served as a diplomat for Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

and other countries. Horthy married Magdolna Purgly de Jószáshely in Arad in 1901. They had 4 children: Magdolna (1902), Paula (1903), István

István () is a Hungarian language equivalent of the name Stephen or Stefan. It may refer to:

People with the given name Nobles, palatines and judges royal

* Stephen I of Hungary (c. 975–1038), last grand prince of the Hungarians and first ki ...

(1904) and Miklós Miklós () is a given name or surname, the Hungarian form of the Greek (English ''Nicholas''), and may refer to:

In Hungarian politics

* Miklós Bánffy, Hungarian nobleman, politician, and novelist

* Miklós Horthy, Regent of the Kingdom of Hun ...

(1907). From 1911 until 1914, he was a naval aide-de-camp to Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the Grand title of the Emperor of Austria, other states of the Habsburg m ...

, for whom he had a great respect.

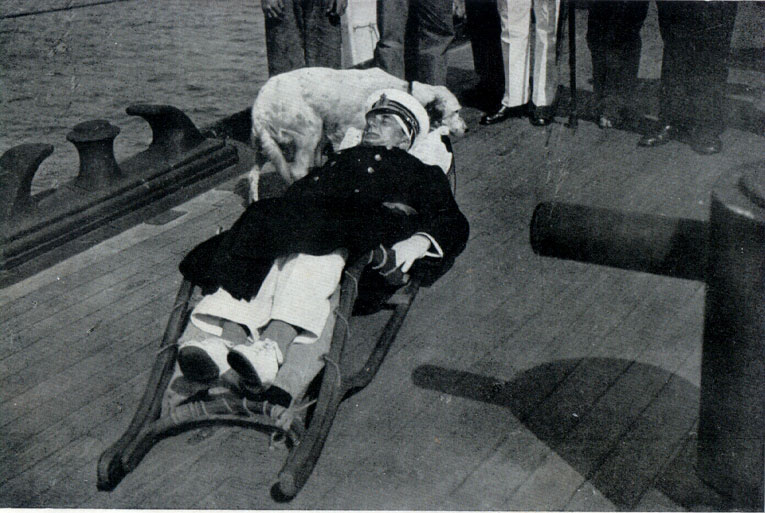

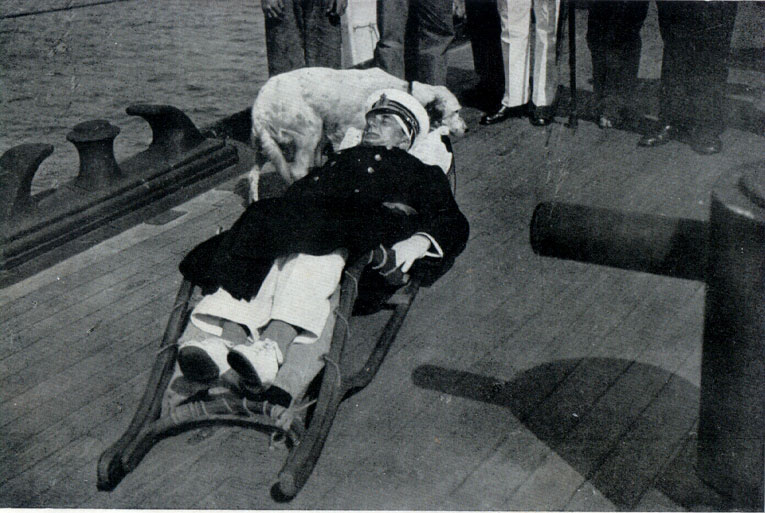

At the beginning of World War I, Horthy was commander of the pre-dreadnought battleship . In 1915, he earned a reputation for boldness while commanding the new light cruiser . He planned the 1917 attack on the Otranto Barrage

The Otranto Barrage was an Allied naval blockade of the Otranto Straits between Brindisi in Italy and Corfu on the Greek side of the Adriatic Sea in the First World War. The blockade was intended to prevent the Austro-Hungarian Navy from escap ...

, which resulted in the Battle of the Strait of Otranto, the largest naval engagement of the war in the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

. A consolidated British, French and Italian fleet met the Austro-Hungarian force. Despite the numerical superiority of the Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

fleet, the Austrian force emerged from the battle victorious. The Austrian fleet remained relatively unscathed, however, Horthy was wounded. After the Cattaro mutiny of February 1918, Emperor Charles I of Austria

Charles I or Karl I (german: Karl Franz Josef Ludwig Hubert Georg Otto Maria, hu, Károly Ferenc József Lajos Hubert György Ottó Mária; 17 August 18871 April 1922) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary (as Charles IV, ), King of Croatia, ...

selected Horthy over many more senior commanders as the new Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Fleet in March 1918. In June, Horthy planned another attack on Otranto, and in a departure from the cautious strategy of his predecessors, he committed the empire's battleships to the mission. While sailing through the night, the dreadnought met Italian MAS torpedo boats and was sunk, causing Horthy to abort the mission. He managed to preserve the rest of the empire's fleet until he was ordered by Emperor Charles to surrender it to the new State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs

The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs ( sh, Država Slovenaca, Hrvata i Srba / ; sl, Država Slovencev, Hrvatov in Srbov) was a political entity that was constituted in October 1918, at the end of World War I, by Slovenes, Croats and Serbs ( ...

(the predecessor of Yugoslavia) on 31 October.

The end of the war saw Hungary turned into a landlocked nation, and with that, the new government had little need for Horthy's naval expertise. He retired with his family to his private estate at Kenderes.

Dates of rank and assignments

* 1896 ''

* 1896 ''Fregattenleutnant

''Fregattenleutnant'' ( hu, Fregatthadnagy; ) was an officer rank in the Austro-Hungarian Navy. It was equivalent to Oberleutnant of the Austro-Hungarian Army, as well to Oberleutnant zur See of the Imperial German Navy. Pertaining to the moder ...

'' (Frigate Lieutenant) (''fregatthadnagy'' – Sub-Lieutenant)

* 1900 ''Linienschiffleutnant'' (Ship-of-the-Line Lieutenant) (''sorhajóhadnagy'' – Lieutenant)

* January 1901 SMS ''Sperber'' (commander of the vessel)

* 1902 SMS ''Kranich'' (commander of the vessel)

* June 1908 SMS ''Taurus'' (commander of the vessel)

* August 1908 (GDO-Gesamtdetailoffizier-First Officer, temporary)

* 1 January 1909 ''Korvettenkapitän

() is the lowest ranking senior officer in a number of Germanic-speaking navies.

Austro-Hungary

Belgium

Germany

Korvettenkapitän, short: KKpt/in lists: KK, () is the lowest senior officer rank () in the German Navy.

Address

The off ...

'' (Corvette Captain) (''korvettkapitány'' – Lieutenant-Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

)

* 1 November 1909 aide-de-camp to Emperor Franz Josef

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 2 December 1848 until his ...

* 1 November 1911 ''Fregattenkapitän

Fregattenkapitän, short: FKpt / in lists: FK, () is the middle field officer rank () in the German Navy.

Address

In line with ZDv 10/8, the official manner of formally addressing military personnel holding the rank of ''Fregattenkapitän'' ...

'' (Frigate Captain) (''fregattkapitány'' – Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

)

* December 1912 March 1913 (commander of the vessel)

* 20 January 1914 ''Linienschiffskapitän

Captain is the name most often given in English-speaking navies to the rank corresponding to command of the largest ships. The rank is equal to the army rank of colonel and air force rank of group captain.

Equivalent ranks worldwide includ ...

'' (Ship-of-the-Line Captain) (''sorhajókapitány'' – Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

)

* August 1914 (commander of the vessel)

* December 1914 (commander of the vessel)

* 1 February 1918 (commander of the vessel)

* 27 February 1918 ''Konteradmiral

''Konteradmiral'', abbreviated KAdm or KADM, is the second lowest naval flag officer rank in the German Navy. It is equivalent to '' Generalmajor'' in the '' Heer'' and ''Luftwaffe'' or to '' Admiralstabsarzt'' and ''Generalstabsarzt'' in the '' ...

'' (''ellentengernagy'' – Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

)

* 27 February 1918 appointed (last) Commander in Chief of the fleet (over 11 admirals and 24 senior ''Linienschiffskapitän'') by Emperor Karl I

Charles I or Karl I (german: Karl Franz Josef Ludwig Hubert Georg Otto Maria, hu, Károly Ferenc József Lajos Hubert György Ottó Mária; 17 August 18871 April 1922) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary (as Charles IV, ), King of Croatia, ...

* 30 October 1918 ''Vizeadmiral

(abbreviated VAdm) is a senior naval flag officer rank in several German-speaking countries, equivalent to Vice admiral.

Austria-Hungary

In the Austro-Hungarian Navy there were the flag-officer ranks ''Kontreadmiral'' (also spelled ''Kont ...

'' (''altengernagy'' – Vice Admiral)

Interwar period, 1919–1939

Historians agree on the conservatism of interwar Hungary. HistorianIstván Deák

István Deák (born 11 May 1926) is a Hungarian-born American historian, author and academic. He is a specialist in modern Europe, with special attention to Germany and Hungary.

Life and work

Deák was born at Székesfehérvár, Hungary into ...

states:

:Between 1919 and 1944 Hungary was a rightist country. Forged out of a counter-revolutionary heritage, its governments advocated a "nationalist Christian" policy; they extolled heroism, faith, and unity; they despised the French Revolution, and they spurned the liberal and socialist ideologies of the 19th century. The governments saw Hungary as a bulwark against Bolshevism and bolshevism's instruments: socialism, cosmopolitanism, and Freemasonry. They perpetrated the rule of a small clique of aristocrats, civil servants, and army officers, and surrounded with adulation by the head of the state, the counterrevolutionary Admiral Horthy.

Commander of the National Army

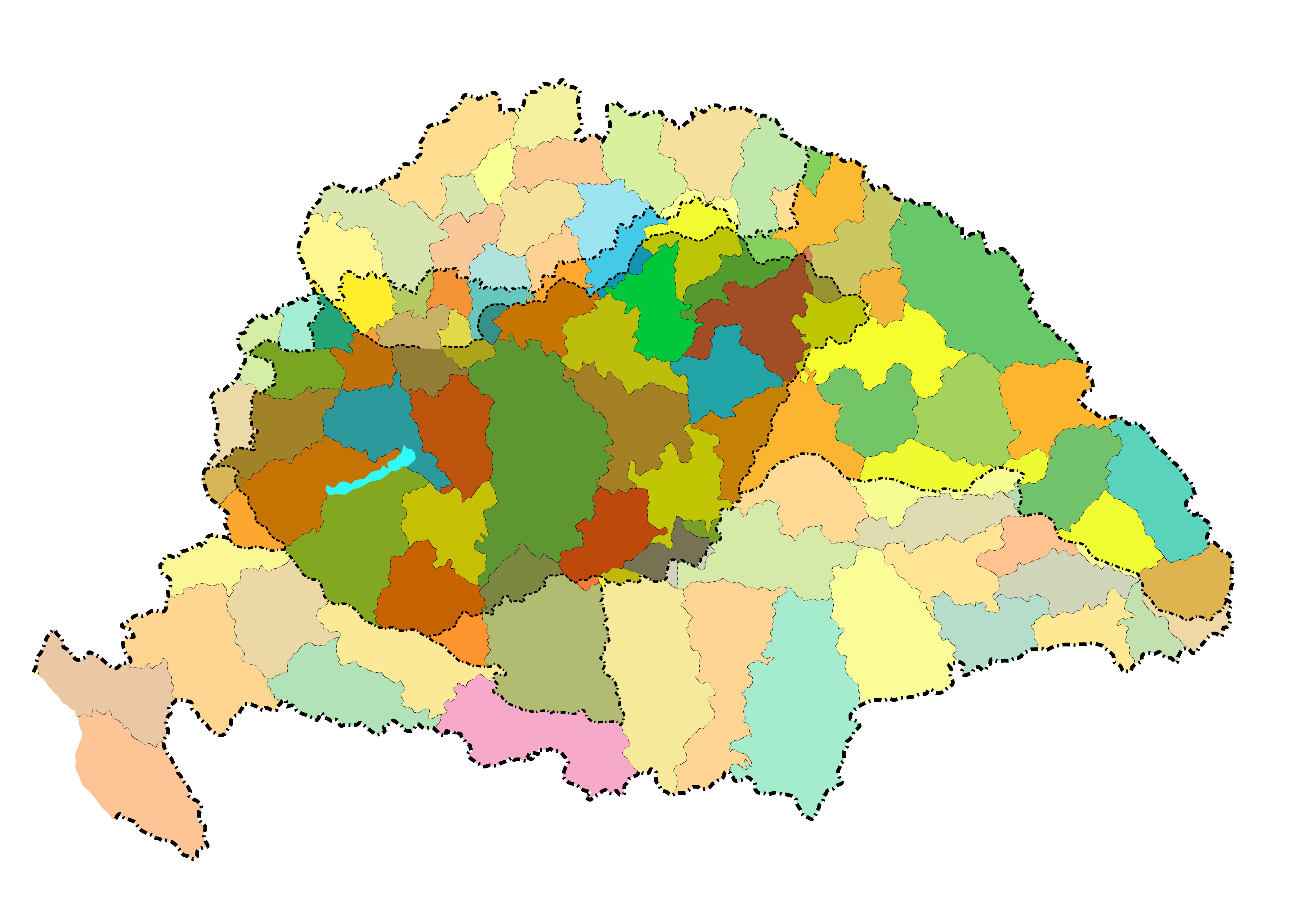

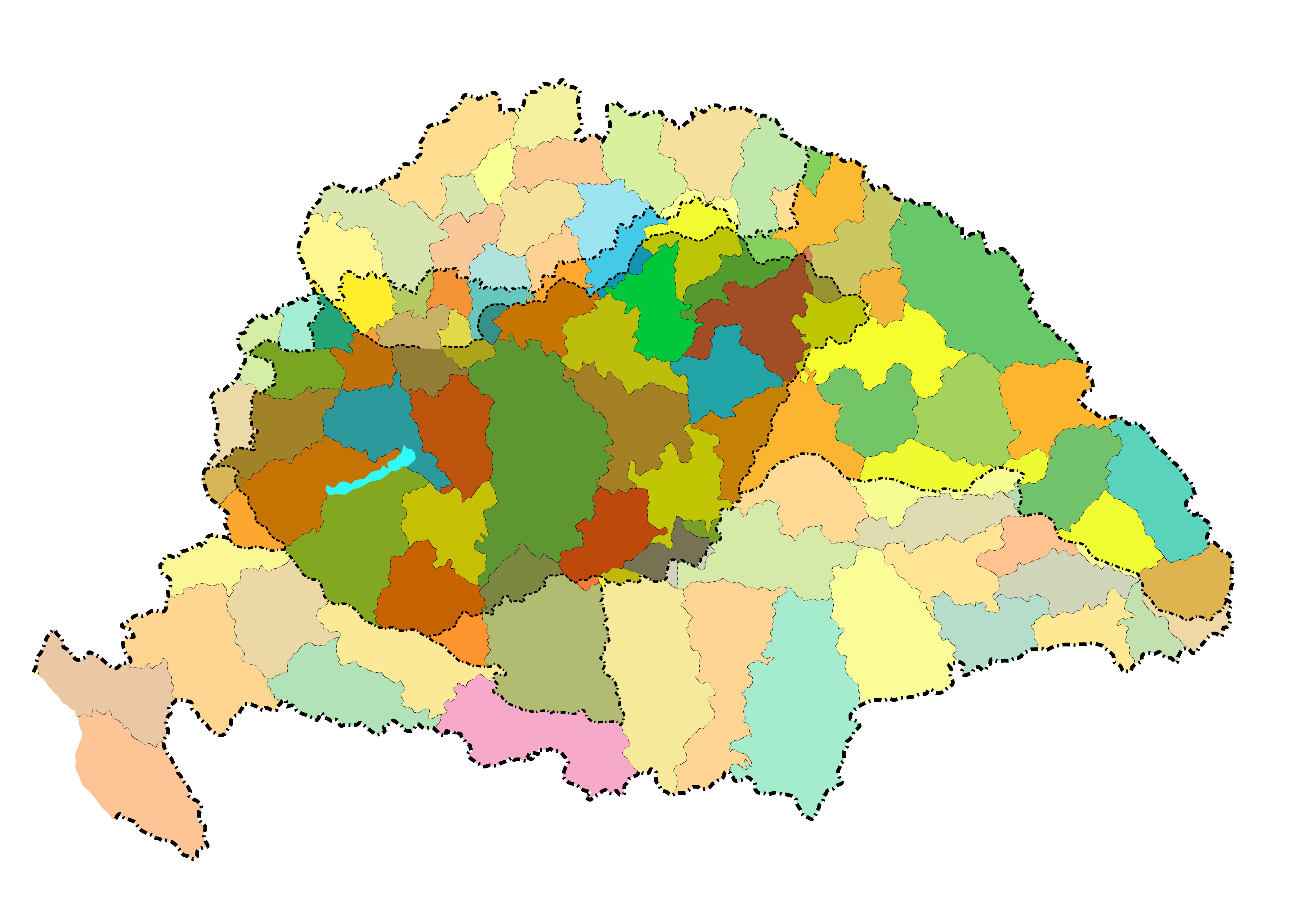

Two national traumas that followed the First World War profoundly shaped the spirit and future of the Hungarian nation. The first was the loss, as dictated by theAllies of World War I

The Allies of World War I, Entente Powers, or Allied Powers were a coalition of countries led by France, the United Kingdom, Russia, Italy, Japan, and the United States against the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Em ...

, of large portions of Hungarian territory that had bordered other countries. These were lands that had belonged to Hungary (then part of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

) but were now ceded mainly to Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

. The excisions, eventually ratified in the Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (french: Traité de Trianon, hu, Trianoni békeszerződés, it, Trattato del Trianon) was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in ...

of 1920, cost Hungary two-thirds of its territory and one-third of its native Hungarian speakers; this dealt the population a terrible psychological blow. The second trauma began in March 1919, when Communist leader Béla Kun

Béla Kun (born Béla Kohn; 20 February 1886 – 29 August 1938) was a Hungarian communist revolutionary and politician who governed the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. After attending Franz Joseph University at Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napoc ...

seized power in the capital, Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

, after the first proto-democratic government in Hungary faltered.

Kun and his henchmen proclaimed a

Kun and his henchmen proclaimed a Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Szocialista Szövetséges Tanácsköztársaság) (due to an early mistranslation, it became widely known as the Hungarian Soviet Republic in English-language sources ( ...

and promised the restoration of Hungary's former grandeur. Instead, his efforts at reconquest failed, and Hungarians were treated to Soviet-style repression in the form of armed gangs who intimidated or murdered enemies of the regime. This period of violence came to be known as the Red Terror

The Red Terror (russian: Красный террор, krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It started in lat ...

.

Within weeks of his coup, Kun's popularity plummeted. On 30 May 1919, anti-communist politicians formed a counter-revolutionary government in the southern city of Szeged

Szeged ( , ; see also #Etymology, other alternative names) is List of cities and towns of Hungary#Largest cities in Hungary, the third largest city of Hungary, the largest city and regional centre of the Southern Great Plain and the county seat ...

, which was occupied by French forces at the time. There, Gyula Károlyi

Gyula Count Károlyi de Nagykároly in English: Julius Károlyi (7 May 1871 in Baktalórántháza – 23 April 1947) was a conservative Hungarian politician who served as Prime Minister of Hungary from 1931 to 1932. He had previously been prime ...

, the prime minister of the counter-revolutionary government, asked former Admiral Horthy, still considered a war hero, to be the Minister of War in the new government and take command of a counter-revolutionary force that would be named the National Army ( hu, Nemzeti Hadsereg). Horthy consented, and he arrived in Szeged on 6 June. Soon afterward, because of orders from the Allied powers, a cabinet was reformed, and Horthy was not given a seat in it. Undaunted, Horthy managed to retain control of the National Army by detaching the army command from the War Ministry.

After the Communist government collapsed and its leaders fled, French-supported Romanian forces entered Budapest on 6 August 1919. In retaliation for the Red Terror

The Red Terror (russian: Красный террор, krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It started in lat ...

, reactionary crews now exacted revenge in a two-year wave of violent repression known today as the White Terror

White Terror is the name of several episodes of mass violence in history, carried out against anarchists, communists, socialists, liberals, revolutionaries, or other opponents by conservative or nationalist groups. It is sometimes contrasted wit ...

. These reprisals were organized and carried out by officers of Horthy's National Army, particularly Pál Prónay

Pál Prónay de Tótpróna et Blatnicza (November 2, 1874 – 1947 or 1948) was a Hungarian reactionary and paramilitary commander in the years following the First World War. He is considered to have been the most brutal of the Hungarian Natio ...

,Patai, Raphael, ''The Jews of Hungary'', Wayne State University Press, pp. 468–469 Gyula Ostenburg-Moravek and Iván Héjjas

Iván Héjjas (19 January 1890 – December 1950) was a Hungarian anti-communist soldier and paramilitary commander in the years following the First World War. He played eminent role in the anti-communist and anti-Semitic purges and massacres ...

.Bodó, Béla: ''Paramilitary Violence in Hungary After the First World War'', East European Quarterly, No. 2, Vol. 38, 22 June 2004 Their victims were primarily communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a so ...

, social democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

, and Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

. Most Hungarian Jews were not supporters of the Bolsheviks, but much of the leadership of the Hungarian Soviet Republic had been young Jewish intellectuals, and anger about the Communist revolution easily translated into anti-Semitic hostility.

In Budapest, Prónay installed his unit in the Hotel Britannia, where the group swelled to battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

size. Their program of vicious attacks continued; they planned a citywide pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

against the Jews until Horthy found out and put a stop to it. In his diary, Prónay reported that Horthy:reproached me for the many Jewish corpses found in the various parts of the country, especially in the Transdanubia. This, he emphasized, gave the foreign press extra ammunitions against us. He told me that we should stop harassing small Jews; instead, we should kill some big (Kun government) Jews such as Somogyi or Vázsonyi – these people deserve punishment much more... in vain, I tried to convince him that the liberal papers would be against us anyway, and it did not matter that we killed only one Jew or we killed them allThe degree of Horthy's responsibility for the excesses of Prónay is disputed. On several occasions, Horthy reached out to stop Prónay from a particularly excessive burst of anti-Jewish cruelty, and the Jews of Pest went on record absolving Horthy of the White Terror as early as the fall of 1919 when they released a statement disavowing the Kun revolution and blaming the terror on a few units within the National Army. Horthy has never been found to have personally engaged in White Terror atrocities. But his American biographer Thomas L. Sakmyster concluded that he "tacitly supported the right-wing officer detachments" who carried out the terror; Horthy called them "my best men". The admiral also had practical reasons for overlooking the terror his officers wrought, since he needed the dedicated officers to help stabilize the country. Nevertheless, it was at least another year before the terror died down. In the summer of 1920, Horthy's government took measures to rein in and eventually disperse the reactionary battalions. Prónay managed to undermine these measures, but only for a short time. Prónay was put on trial for extorting a wealthy Jewish politician, and for "insulting the President of the Parliament" by trying to cover up the extortion. Found guilty on both charges, Prónay was now a liability and an embarrassment. His command was revoked, and he was denounced as a common criminal on the floor of the Hungarian parliament. After serving short jail sentences, Prónay tried to convince Horthy to restore his battalion command. The Prónay Battalion lingered for a few months more under the command of a junior officer, but the government officially dissolved the unit in January 1922 and expelled its members from the army. Prónay entered politics as a member of the government's right-wing opposition. In the 1930s, he sought and failed to emulate the Nazis by generating a Hungarian fascist mass movement. In 1932, he was charged with incitement, sentenced to six months in prison, and stripped of his rank of lieutenant colonel. Prónay would support the pro-Nazi Arrow Cross and lead attacks on Jews before being captured by Soviet troops sometime during or after the

Battle of Budapest

The Siege of Budapest or Battle of Budapest was the 50-day-long encirclement by Soviet and Romanian forces of the Hungarian capital of Budapest, near the end of World War II. Part of the broader Budapest Offensive, the siege began when Budap ...

of 1944–45, dying in captivity in 1947/48.

Precisely how much Horthy knew about the excesses of the White Terror is not known. Horthy himself declined to apologize for the savagery of his officer detachments, writing later, "I have no reason to gloss over deeds of injustice and atrocities committed when an iron broom alone could sweep the country clean." He endorsed Edgar von Schmidt-Pauli's poetic justification of the White reprisals ("Hell let loose on earth cannot be subdued by the beating of angels' wings") remarking, "the Communists in Hungary, willing disciples of the Russian Bolshevists, had indeed let hell loose."

The International Committee of the Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; french: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge) is a humanitarian organization which is based in Geneva, Switzerland, and it is also a three-time Nobel Prize Laureate. State parties (signato ...

(ICRC) in an internal report by delegate George Burnier, stated the following in April 1920:There are two distinct military organizations in Hungary: the national army and a kind of civil guard which was formed when the communist régime fell. It is the latter that has been responsible for all the reprehensible acts committed. The Government managed to regain control of these organizations only a few weeks ago. They are now well-disciplined and collaborate with the municipal police forces.This deep hostility toward Communism would be the more lasting legacy of Kun's abortive revolution. It was a conviction shared by Horthy and his country's ruling class that would help drive Hungary into a fateful alliance with Adolf Hitler.

The nation of the Hungarians loved and admired Budapest, which became its polluter in the last years. Here, on the banks of the Danube, I arraign her. This city has disowned her thousand years of tradition, she has dragged theHoly Crown The Holy Crown of Hungary ( hu, Szent Korona; sh, Kruna svetoga Stjepana; la, Sacra Corona; sk, Svätoštefanská koruna , la, Sacra Corona), also known as the Crown of Saint Stephen, named in honour of Saint Stephen I of Hungary, was the c ...and thenational colors National colours are frequently part of a country's set of national symbols. Many states and nations have formally adopted a set of colours as their official "national colours" while others have ''de facto'' national colours that have become well ...in the dust, she has clothed herself in red rags. The finest of the nation she threw into dungeons or drove into exile. She laid in ruin our property and wasted our wealth. Yet the nearer we approached to this city, the more rapidly did the ice in our hearts melt. We are now ready to forgive her.

Following the pressure of the Allied powers, Romanian troops finally evacuated Hungary on 25 February 1920.

Following the pressure of the Allied powers, Romanian troops finally evacuated Hungary on 25 February 1920.

Regent

On 1 March 1920, the National Assembly of Hungary re-established theKingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

. It was apparent that the Allies of World War I would not accept any return of King Charles IV (the former Austro-Hungarian emperor) from exile. Instead, with National Army officers controlling the parliament building, the assembly voted to install Horthy as Regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

; he defeated Count Albert Apponyi

Albert György Gyula Mária Apponyi, Count of Nagyappony ( hu, Gróf nagyapponyi Apponyi Albert György Gyula Mária; 29 May 18467 February 1933) was a Hungarian aristocrat and politician. He was a board member of the Hungarian Academy of Sc ...

by a vote of 131 to 7.

Bishop Ottokár Prohászka

Ottokár Prohászka ( hu, Prohászka Ottokár; 10 October 1858 – 2 April 1927) was a Hungarian Roman Catholic theologian and Bishop of Székesfehérvár from 1905 until his death.

Prohászka was born in Nyitra (today Nitra, Slovakia). He was ...

then led a small delegation to meet Horthy, announcing, "Hungary's Parliament has elected you Regent! Would it please you to accept the office of Regent of Hungary?" To their astonishment, Horthy declined, unless the powers of the office were expanded. As Horthy stalled, the politicians gave in to his demands and granted him "the general prerogatives of the king, with the exception of the right to name titles of nobility and of the patronage of the Church." The prerogatives he was given included the power to appoint and dismiss prime ministers, to convene and dissolve parliament, and to command the armed forces

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

. With those sweeping powers guaranteed, Horthy took the oath of office. He was styled ''His Serene Highness the Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary'' ( hu, Ő Főméltósága a Magyar Királyság Kormányzója). (Charles I did try to regain his throne twice; see Charles IV of Hungary's attempts to retake the throne

After Miklós Horthy was chosen Regent of Hungary on 1 March 1920, Charles I of Austria, who reigned in Hungary as Charles IV, made two unsuccessful attempts to retake the throne. His attempts are also called the "First" and "Second Royal ''coups ...

for more details.)

The Hungarian state was legally a kingdom, but it had no king, as the Allied powers would not have tolerated any reinstatement of the Habsburg dynasty. The country retained its parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

following the dissolution of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, with a prime minister appointed as head of government. As head of state, Horthy retained significant influence through his constitutional powers and the loyalty of his ministers to the crown. Although his involvement in drafting legislation was minuscule, he nevertheless had the ability to ensure that laws passed by the Hungarian parliament conformed to his political preferences.

Seeking redress for the Treaty of Trianon

The first decade of Horthy's reign was primarily consumed by stabilizing the Hungarian economy and political system. Horthy's chief partner in these efforts was his prime minister

The first decade of Horthy's reign was primarily consumed by stabilizing the Hungarian economy and political system. Horthy's chief partner in these efforts was his prime minister István Bethlen

Count István Bethlen de Bethlen (8 October 1874, Gernyeszeg – 5 October 1946, Moscow) was a Hungarian aristocrat and statesman and served as prime minister from 1921 to 1931.

Early life

The scion of an old Bethlen de Bethlen noble fam ...

. It was commonly known that Horthy was an Anglophile

An Anglophile is a person who admires or loves England, its people, its culture, its language, and/or its various accents.

Etymology

The word is derived from the Latin word ''Anglii'' and Ancient Greek word φίλος ''philos'', meaning "frien ...

, and British political and economic support played a significant role in the stabilization and consolidation of the early Horthy era in the Kingdom of Hungary.

Bethlen sought to stabilize the economy while building alliances with weaker nations that could advance Hungary's cause. That cause was, primarily, reversing the losses of the Treaty of Trianon. The humiliations of the Trianon treaty continued to occupy a central place in Hungarian foreign policy and the popular imagination. The indignant anti-Trianon slogan "Nem, nem soha!" ("No, no never!") became a ubiquitous motto of Hungarian outrage. When in 1927 the British newspaper magnate Lord Rothermere

Viscount Rothermere, of Hemsted in the county of Kent, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1919 for the press lord Harold Harmsworth, 1st Baron Harmsworth. He had already been created a baronet, of Horsey in th ...

denounced the partitions ratified at Trianon in the pages of his ''Daily Mail'', an official letter of gratitude was eagerly signed by 1.2 million Hungarians.

But Hungary's stability was precarious, and the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

derailed much of Bethlen's economic balance. Horthy replaced him with an old reactionary confederate from his Szeged days: Gyula Gömbös. Gömbös was an outspoken anti-Semite and a budding fascist. Although he agreed to Horthy's demands that he temper his anti-Jewish rhetoric and work amicably with Hungary's large Jewish professional class, Gömbös's tenure began swinging Hungary's political mood powerfully rightward. He strengthened Hungary's ties to Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

's Italian fascist state. Fatefully, when Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

took power in Germany in 1933, he found in Gömbös an admiring and obliging colleague. John Gunther

John Gunther (August 30, 1901 – May 29, 1970) was an American journalist and writer.

His success came primarily by a series of popular sociopolitical works, known as the "Inside" books (1936–1972), including the best-selling ''Insid ...

stated that Horthy,

Gömbös rescued the failing economy by securing trade guarantees from Germany – a strategy that positioned Germany as Hungary's primary trading partner and tied Hungary's future even more tightly to Hitler's. He also assured Hitler that Hungary would quickly become a one-party state modeled on the Nazi party control of Germany. Gömbös died in 1936 before he realized his most extreme goals, but he left his nation headed into a firm partnership with the German dictator.

World War II and the Holocaust

Uneasy alliance

Hungary now entered into intricate political maneuvers with the regime of Adolf Hitler, and Horthy began to play a greater and more public role in navigating Hungary along this dangerous path. For Horthy, Hitler served as a bulwark against Soviet encroachment or invasion. Horthy was obsessed with the Communist threat. One American diplomat remarked that Horthy's anti-communist tirades were so common and ferocious that diplomats "discounted it as a phobia".

Horthy clearly saw his country as trapped between two stronger powers, both of them dangerous; evidently, he considered Hitler to be the more manageable of the two, at least at first. Hitler was able to wield greater influence over Hungary than the Soviet Union could – not only as of the country's major trading partner but also because he could assist with two of Horthy's key ambitions: maintaining Hungarian sovereignty and satisfying the nationwide yearning to recover former Hungarian lands. Horthy's strategy was one of cautious, sometimes even a grudging, alliance. The means by which the regent granted or resisted Hitler's demands, especially with regard to Hungarian military action and the treatment of Hungary's Jews, remain the central criteria by which his career has been judged. Horthy's relationship with Hitler was, by his own account, a tense one – largely due, he said, to his unwillingness to bend his nation's policies to the German leader's desires.

Horthy's attitude to Hitler was ambivalent. On one hand, Hungary was an

For Horthy, Hitler served as a bulwark against Soviet encroachment or invasion. Horthy was obsessed with the Communist threat. One American diplomat remarked that Horthy's anti-communist tirades were so common and ferocious that diplomats "discounted it as a phobia".

Horthy clearly saw his country as trapped between two stronger powers, both of them dangerous; evidently, he considered Hitler to be the more manageable of the two, at least at first. Hitler was able to wield greater influence over Hungary than the Soviet Union could – not only as of the country's major trading partner but also because he could assist with two of Horthy's key ambitions: maintaining Hungarian sovereignty and satisfying the nationwide yearning to recover former Hungarian lands. Horthy's strategy was one of cautious, sometimes even a grudging, alliance. The means by which the regent granted or resisted Hitler's demands, especially with regard to Hungarian military action and the treatment of Hungary's Jews, remain the central criteria by which his career has been judged. Horthy's relationship with Hitler was, by his own account, a tense one – largely due, he said, to his unwillingness to bend his nation's policies to the German leader's desires.

Horthy's attitude to Hitler was ambivalent. On one hand, Hungary was an irredentist

Irredentism is usually understood as a desire that one state annexes a territory of a neighboring state. This desire is motivated by ethnic reasons (because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to the population of the parent sta ...

state that refused to accept the frontiers imposed by the Treaty of Trianon. Furthermore, the three states with which Hungary had territorial disputes, namely Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Romania, were all allies of France, so a German-Hungarian alliance seemed logical. On the other hand, Admiral Horthy was a good navalist who believed that sea power was the most important factor in war. He felt that Britain, as the world's greatest sea power, would inevitably defeat Germany should another war begin.Eby, Cecil ''Hungary at War: Civilians and Soldiers in World War II'', University Park: Penn State Press, 2007 page 9. During a meeting with Hitler in 1935, Horthy was well pleased that Hitler informed him that he wanted Germany and Hungary to partition Czechoslovakia, but Horthy went on to tell Hitler that he must be careful not to do anything that might cause an Anglo-German war because British sea power would sooner or later cause the defeat of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. Horthy was always torn between his belief that an alliance with Germany was the only way to revise Trianon and his belief that war against the international order could only end in defeat.

In August 1938, when Horthy, his wife, and some Hungarian politicians took a special train from Budapest to Germany, SA and other National Socialist

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

formations ceremonially welcomed the delegation at the Passau

Passau (; bar, label=Central Bavarian, Båssa) is a city in Lower Bavaria, Germany, also known as the Dreiflüssestadt ("City of Three Rivers") as the river Danube is joined by the Inn from the south and the Ilz from the north.

Passau's popu ...

train station. The train then continued to Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

for the christening of the German cruiser ''Prinz Eugen''.

During his ensuing state visit, Hitler asked Horthy for troops and matériel to participate in Germany's planned invasion of Czechoslovakia. In exchange, Horthy later reported, "He gave me to understand that as a reward we should be allowed to keep the territory we had invaded." Horthy said he declined, insisting to Hitler that Hungary's claims on the disputed lands should be settled by peaceful means.

Three months later, after the

Three months later, after the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

put control of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

in Hitler's hands, by the First Vienna Award

The First Vienna Award was a treaty signed on 2 November 1938 pursuant to the Vienna Arbitration, which took place at Vienna's Belvedere Palace. The arbitration and award were direct consequences of the previous month's Munich Agreement, which ...

Hungary annexed some of the south-eastern parts of Czechoslovakia. Horthy enthusiastically rode into the re-acquired territories at the head of his troops, greeted by emotional ethnic Hungarians: "As I passed along the roads, people embraced one another, fell upon their knees, and wept with joy because liberation had come to them at last, without war, without bloodshed." But as "peaceful" as this annexation was, and as just as it may have seemed to many Hungarians, it was a dividend of Hitler's brinksmanship and threats of war, in which Hungary was now inextricably complicit. Hungary was now committed to the Axis agenda: on 24 February 1939, it joined the Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (Com ...

, and on 11 April, it withdrew from the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. American journalists began to refer to Hungary as "the jackal of Europe".

This combination of menace and reward drifted Hungary closer to the status of a Nazi client state. In March 1939, when Hitler took what remained of Czechoslovakia by force, Hungary was allowed to annex Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia ( rue, Карпатьска Русь, Karpat'ska Rus'; uk, Закарпаття, Zakarpattia; sk, Podkarpatská Rus; hu, Kárpátalja; ro, Transcarpatia; pl, Zakarpacie); cz, Podkarpatská Rus; german: Karpatenukrai ...

. After a conflict with the First Slovak Republic

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

during the Slovak–Hungarian War

The Slovak–Hungarian War, or Little War ( hu, Kis háború, sk, Malá vojna), was a war fought from 23 March to 31 March 1939 between the First Slovak Republic and Hungary in eastern Slovakia.

Prelude

After the Munich Pact, which weakened C ...

of 1939, Hungary gained further territories. In August 1940, Hitler intervened on Hungary's behalf once again. After the failed Hungarian-Romanian negotiations, Hungary annexed Northern Transylvania

Northern Transylvania ( ro, Transilvania de Nord, hu, Észak-Erdély) was the region of the Kingdom of Romania that during World War II, as a consequence of the August 1940 territorial agreement known as the Second Vienna Award, became part of ...

from Romania by the Second Vienna Award

The Second Vienna Award, also known as the Vienna Diktat, was the second of two territorial disputes that were arbitrated by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. On 30 August 1940, they assigned the territory of Northern Transylvania, including all ...

.

But despite their cooperation with the Nazi regime, Horthy and his government would be better described as "conservative authoritarian" than "fascist". Certainly, Horthy was as hostile to the home-grown fascist and ultra-nationalist movements that emerged in Hungary between the wars (particularly the

But despite their cooperation with the Nazi regime, Horthy and his government would be better described as "conservative authoritarian" than "fascist". Certainly, Horthy was as hostile to the home-grown fascist and ultra-nationalist movements that emerged in Hungary between the wars (particularly the Arrow Cross Party

The Arrow Cross Party ( hu, Nyilaskeresztes Párt – Hungarista Mozgalom, , abbreviated NYKP) was a far-right Hungarian ultranationalist party led by Ferenc Szálasi, which formed a government in Hungary they named the Government of National ...

) as he was to Communism. The Arrow Cross leader, Ferenc Szálasi

Ferenc Szálasi (; 6 January 1897 – 12 March 1946), the leader of the Arrow Cross Party – Hungarist Movement, became the "Leader of the Nation" (''Nemzetvezető'') as head of state and simultaneously prime minister of the Kingdom of Hungary' ...

, was repeatedly imprisoned at Horthy's command.

John F. Montgomery, who served in Budapest as U.S. ambassador from 1933 to 1941, openly admired this side of Horthy's character and reported the following incident in his memoir: in March 1939, Arrow Cross supporters disrupted a performance at the Budapest opera house

The Hungarian State Opera House ( hu, Magyar Állami Operaház) is a neo-Renaissance opera house located in central Budapest, on Andrássy út. Originally known as the Hungarian Royal Opera House, it was designed by Miklós Ybl, a major figure o ...

by chanting "Justice for Szálasi!" loud enough for the regent to hear. A fight broke out, and when Montgomery went to take a closer look, he discovered that:two or three men were on the floor and he orthyhad another by the throat, slapping his face and shouting what I learned afterward was: "So you would betray your country, would you?" The Regent was alone, but he had the situation in hand.... The whole incident was typical not only of the Regent's deep hatred of alien doctrine, but of the kind of man he is. Although he was around seventy-two years of age, it did not occur to him to ask for help; he went right ahead like a skipper with a mutiny on his hands.

And yet, by the time of this episode, Horthy had allowed his government to give in to Nazi demands that the Hungarians enact laws restricting the lives of the country's Jews. The first Hungarian anti-Jewish Law, in 1938, limited the number of Jews in the professions, the government, and commerce to twenty percent, and the second reduced it to five percent the following year; 250,000 Hungarian Jews lost their jobs as a result. A "Third Jewish Law" of August 1941 prohibited Jews from marrying non-Jews and defined anyone having two Jewish grandparents as "racially Jewish". A Jewish man who had non-marital sex with a "decent non-Jewish woman resident in Hungary" could be sentenced to three years in prison.

Horthy's personal views on Jews and their role in Hungarian society are the subjects of some debate. In an October 1940 letter to Prime Minister

And yet, by the time of this episode, Horthy had allowed his government to give in to Nazi demands that the Hungarians enact laws restricting the lives of the country's Jews. The first Hungarian anti-Jewish Law, in 1938, limited the number of Jews in the professions, the government, and commerce to twenty percent, and the second reduced it to five percent the following year; 250,000 Hungarian Jews lost their jobs as a result. A "Third Jewish Law" of August 1941 prohibited Jews from marrying non-Jews and defined anyone having two Jewish grandparents as "racially Jewish". A Jewish man who had non-marital sex with a "decent non-Jewish woman resident in Hungary" could be sentenced to three years in prison.

Horthy's personal views on Jews and their role in Hungarian society are the subjects of some debate. In an October 1940 letter to Prime Minister Pál Teleki

Count Pál János Ede Teleki de Szék (1 November 1879 – 3 April 1941) was a Hungarian politician who served as Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1920 to 1921 and from 1939 to 1941. He was also an expert in geography, a un ...

, Horthy echoed a widespread national sentiment: that Jews enjoyed too much success in commerce, the professions, and industry – success that needed to be curtailed:As regards the Jewish problem, I have been an anti-Semite throughout my life. I have never had contact with Jews. I have considered it intolerable that here in Hungary everything, every factory, bank, large fortune, business, theatre, press, commerce, etc. should be in Jewish hands, and that the Jew should be the image reflected of Hungary, especially abroad. Since, however, one of the most important tasks of the government is to raise the standard of living, i.e., we have to acquire wealth, it is impossible, in a year or two, to replace the Jews, who have everything in their hands, and to replace them with incompetent, unworthy, mostly big-mouthed elements, for we should become bankrupt. This requires a generation at least.

War

The

The Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

was gradually drawn into the war itself. In 1939 and 1940, Hungarian volunteers were sent to Finland's Winter War

The Winter War,, sv, Vinterkriget, rus, Зи́мняя война́, r=Zimnyaya voyna. The names Soviet–Finnish War 1939–1940 (russian: link=no, Сове́тско-финская война́ 1939–1940) and Soviet–Finland War 1 ...

, but did not have time to partake in the fighting before the end of the war. In April 1941, Hungary became, in effect, a member of the Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

. Hungary permitted Hitler to send troops across Hungarian territory for the invasion of Yugoslavia

The invasion of Yugoslavia, also known as the April War or Operation 25, or ''Projekt 25'' was a German-led attack on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers which began on 6 April 1941 during World War II. The order for the invasion was p ...

and ultimately sent its own troops to claim its share of the dismembered Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 unt ...

. Prime Minister Pál Teleki

Count Pál János Ede Teleki de Szék (1 November 1879 – 3 April 1941) was a Hungarian politician who served as Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1920 to 1921 and from 1939 to 1941. He was also an expert in geography, a un ...

, horrified that he had failed to prevent this collusion with the Nazis, despite the fact that he had signed a non-aggression pact with Yugoslavia in December 1940, committed suicide.

In June 1941, the Hungarian government finally yielded to Hitler's demands that the nation contribute to the Axis war effort. On 27 June, Hungary became part of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

and declared war on the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. The Hungarians sent in troops and material only four days after Hitler began his invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941.

Eighteen months later, less well-equipped and less motivated than their German allies, 200,000 troops of the Hungarian Second Army

The Hungarian Second Army (''Második Magyar Hadsereg'') was one of three field armies (''hadsereg'') raised by the Kingdom of Hungary (''Magyar Királyság'') which saw action during World War II. All three armies were formed on March 1, 1940. ...

ended up holding the front on the Don River

The Don ( rus, Дон, p=don) is the fifth-longest river in Europe. Flowing from Central Russia to the Sea of Azov in Southern Russia, it is one of Russia's largest rivers and played an important role for traders from the Byzantine Empire.

Its ...

west of Stalingrad

Volgograd ( rus, Волгогра́д, a=ru-Volgograd.ogg, p=vəɫɡɐˈɡrat), geographical renaming, formerly Tsaritsyn (russian: Цари́цын, Tsarítsyn, label=none; ) (1589–1925), and Stalingrad (russian: Сталингра́д, Stal ...

.

The first massacre of Jewish people from Hungarian territory took place in August 1941, when government officials ordered the deportation of Jews without Hungarian citizenship (principally refugees from other Nazi-occupied countries) to Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

. Roughly 18,000–20,000 of these deportees were slaughtered by Friedrich Jeckeln

Friedrich Jeckeln (2 February 1895 – 3 February 1946) was a German SS commander during the Nazi era. He served as a Higher SS and Police Leader in the occupied Soviet Union during World War II. Jeckeln was the commander of one of the largest ...

and his SS troops; only 2,000–3,000 survived. These killings are known as the Kamianets-Podilskyi Massacre

The Kamianets-Podilskyi massacre was a World War II mass shooting of Jews carried out in the opening stages of Operation Barbarossa, by the German Police Battalion 320 along with Friedrich Jeckeln's ''Einsatzgruppen'', the Hungarian soldiers, a ...

. This event, in which the slaughter of Jews for the first time numbered in the tens of thousands, is considered to be among the first large-scale massacre of the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

. Because of the objections of Hungary's leadership, the deportations were halted.

By early 1942, Horthy was already seeking to put some distance between himself and Hitler's regime. That March, he dismissed the pro-German prime minister László Bárdossy

László Bárdossy de Bárdos (10 December 1890 – 10 January 1946) was a Hungary, Hungarian diplomat and politician who served as Prime Minister of Hungary from April 1941 to March 1942. He was one of the chief architects of Hungary's involve ...

and replaced him with Miklós Kállay, a moderate whom Horthy expected to loosen Hungary's ties to Germany. Kállay successfully sabotaged economic cooperation with Nazi Germany, protected refugees, and prisoners, resisted Nazi pressure regarding Jews, established contact with the Allies and negotiated conditions under which Hungary would switch sides against Germany. However, the Allies were not close enough. When the Germans occupied Hungary in March 1944 Kállay went into hiding. He was finally captured by the Nazis, but was liberated when the war ended.

In September 1942, personal tragedy struck the Hungarian Regent. 37-year-old István Horthy

Vitéz István Horthy de Nagybánya (9 December 1904 – 20 August 1942) was Hungarian regent Admiral Miklós Horthy's eldest son, a politician, and, during World War II, a fighter pilot.

Biography

In his youth, István Horthy and his young ...

, Horthy's eldest son, was killed. István Horthy was the Deputy Regent of Hungary and a Flight Lieutenant in the reserves, 1/1 Fighter Squadron of the Royal Hungarian Air Force

The Hungarian Air Force ( hu, Magyar Légierő), is the air force branch of the Hungarian Defence Forces.

The task of the current Hungarian Air Force is primarily defensive purposes. The flying units of the air force are organised into a single ...

. He was killed when his Hawk ('' Héja'') fighter crashed at an air field near Ilovskoye.

In January 1943, Hungary's enthusiasm for the war effort, never especially high, suffered a tremendous blow. The Soviet army, in the full momentum of its triumphant turnaround after the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II where Nazi Germany and its allies unsuccessfully fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (later re ...

, punched through Romanian troops at a bend in the Don River

The Don ( rus, Дон, p=don) is the fifth-longest river in Europe. Flowing from Central Russia to the Sea of Azov in Southern Russia, it is one of Russia's largest rivers and played an important role for traders from the Byzantine Empire.

Its ...